SU's Ranzan Edits First-Person Account of Civil War's Most Notorious Prison Camp

SALISBURY, MD---From 1864 into 1865, the largest city in Georgia was not Atlanta, but Camp Sumter, a Civil War prison near Andersonville.

SALISBURY, MD---From 1864 into 1865, the largest city in Georgia was not Atlanta, but Camp Sumter, a Civil War prison near Andersonville.

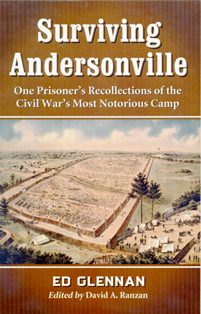

Surviving Andersonville: One Prisoner’s Recollection of the Civil War’s Most Notorious Camp, a first-person account edited by Salisbury University archivist David Ranzan, tells the horrific story of the brutal conditions that existed in the prison from the point of view of Irish immigrant Edward Glennan.

Glennan was a child in 1846, when the Irish Potato Famine forced many to flee Ireland. He immigrated to England with his parents and siblings, spending more than a decade there. By about 1857, the family had saved enough money to travel to the United States, where they sought a new life in the American Midwest.

At the beginning of the Civil War, many Irish-Americans, filled with patriotism for their adopted home, joined the Union Army. Glennan’s experiences in England and the American South gave him more encouragement to sign up than most.

During his time in England, he had heard British soldiers romanticize their time in combat. In addition, he had worked in the South during the winter immediately preceding the war and formed a less-than-favorable opinion of the general attitudes of the men in that part of the nation. He joined the 42nd Illinois Infantry Regiment in 1861.

In fall 1863, he was captured behind Confederate lines and was incarcerated at prisons in Virginia, then transferred to Andersonville, where he endured eight months among some 40,000 other captured federal soldiers, sailors and civilians. A first sergeant with the Union Army, he wrote down his experiences in 1891 while a patient at the Leavenworth National Home in Kansas.

Ranzan first became aware of Glennan’s journal in 2008 while inventorying the archival holdings of SU’s Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture. He discovered second-generation photocopies of the nearly 300 pages of writings among items in the center’s Rose Embry Carey Collection. A resident of Salisbury, Carey is Glennan’s great-grandniece.

“After several days of reading the soldier’s memoir, I was hooked,” said Ranzan. “His narrative illustrated the hardships typical of prisoners of war, but with a personable flair that quickly drew me into his story. The humor, cynicism, honesty, desperation and hatred in his struggle to remain human at a place shrouded in inhumanity and horror drew me in.”

During his time at Camp Sumter, Glennan witnessed hangings and escape attempts, and participated in gambling, trading and rationing. Afflicted with scurvy, he nearly lost his ability to walk.

“Never while our Merciful Creator lets me live and retain my senses can I forget that date, the 20th of March, 1864,” Glennan wrote. “No, if I wanted to, I could not forget it, for I am reminded of it every time I see my features and hair in a glass. Yes, every time I receive a twinge of pain and think to myself, ‘Where did that come from?’ the answer is ‘Andersonville.’ Every time I have to sit down from weakness while walking for exercise and I wonder to myself what make me so weak, again I answer ‘Andersonville.’”

In the end, only his cunning survival skills saved him from the fate of an estimated 13,000 prisoners who were killed during the 14 months Camp Sumter was in operation.

The book represents Ranzan’s third documentary editing project. Others include The Papers of the War Department, 1784-1800 and The Thomas A. Edison Papers.

For more information call 410-543-6030 or visit the SU Web site at www.salisbury.edu.